“Queerness can never define an identity; it can only ever disturb one.” -Lee Edelman,

No Future: Queer Theory and the Death DriveBoy, oh boy—it’s episodes like today’s that make me happy I write a blog that applies post-structural theory to the Dr. Phil Show. After introducing us to Kim and Cory, a teenage couple in a tumultuous marriage with two neglected children, Dr. Phil went on a maniacal crusade. The mission was not to promote family planning or contraceptives, nor was it even to sound the clarion call of abstinence, but instead Dr. Phil pleaded with parents of teens and the teens themselves, begging them to listen as he shouted: you’re not really in love! By the way, this

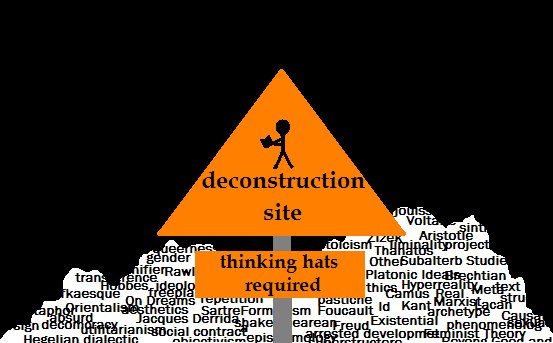

isn’t his first rodeo. As usual, there’s a large body of literature we might wish to consult in order to deconstruct Phil’s sophism. Since it is fairly inconceivable that any teenage lover would listen to this episode without a fit of Romantic giggles, it seems only fair that we pick a theorist who—despite his or her value—would likewise be ignored by Phil. That brings us to queer theorist Lee Edelman and his recent book

No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. But Edelman’s queerness isn’t exactly the queerness that so rarely shows up on the Dr. Phil show. Rather, it’s the queerness that is always somehow present in the Dr. Phil show. As Edelman writes, queerness “names the side of those

not ‘fighting for the children,’ the side outside the consensus by which all politics confirms the absolute value of reproductive futurism” (5). We see this nearly every episode when Dr. Phil says something to his guests like “Your [insert destructive behavior here] would be fine, except you have kids!” or, more subtly, when he makes comments like “it’s time for you guys to grow up and be adults!” Thus, Dr. Phil sets himself up in the most favorable ideological position; he’s the one fighting for the children. His guests are

always the queer ones—man, oh man do they need help—those queer folks who aren’t acting like adults or taking proper care of the kids, their future, their Other-to-come. Surely it is not a coincidence that virtually every episode is in some way an incarnation of a plagued marriage or perverted parent-child relationship. That’s the queerness—the lack of reproductive futurism—that must be mended. At least that’s what Dr. Phil—indeed all politics and society—would have us believe. Edelman sees it differently. To disregard for a moment the specific, non-theoretical children with diaper-rashes and growling stomachs, we can begin to see what Edelman terms the “

sinthomosexual”(33). Building off of the Lacanian concept of the

sinthome, Edelman writes that

sinthomosexuals assert themselves “

against futurity [and] against its propagation, insofar as it would designate an impasse in the passage to the future and, by doing so, would pass beyond, pass through, the saving fantasy futurity denotes” (Ibid). Instead,

sinthomosexuals are “insisting on access to

jouissance in place of access to sense.” (37). In this radical juxtaposition, there is now something wrong with Dr. Phil. He’s the one continuously restaging his “dream of eventual self-realization by endlessly reconstructing, in the mirror of desire, what [he takes] to be reality itself” (79). Of course you’re miserable now, it’s about your children…What? They’re miserable too? Well, then it’s about their children…We need not applaud the guests for mistreating their children, but perhaps they should be congratulated for standing up against the tyranical “belief in a final signifier” and their attempts to undermine “the promise of futurity” (37, 35). Kim and Cory from this “troubled teen love” episode are indeed unfit in many ways. They aren’t great examples of the

sinthomosexuals who triumphantly live for the

jouissance not the unreachable desire of futurity. Of course, Dr. Phil is also not a perfect and blameless reproductive futurist as he steps in with his Texas justice to spank the “children raising children.” The admission that children themselves—traditionally non-sexual and without agency—can be corrupted and destined to an unhappy future is something of a precarious step for Dr. Phil. While certain aspects of mainstream psychology focus on how the curable adult subject was influenced as a child (with the events and impacts reappearing through symptoms as an adult) Dr. Phil has never seemed to agree. At one point Dr. Phil suggested that he should have been involved all along (even before Kim and Cory had their kids) in order to insure a happy childhood and future. Dr. Phil is not promoting

sinthomosexuality or the toned down and mitigated version of reproductive futurism inherent in most psychoanalytic thought—instead he’s demanding to be involved in every conception of the future to come personally (whether it’s queer or not) from the very childish beginning, to the equally childish future that will not end.